Victorian Vacations

Did you know…

Victorian Era Americans were several generations removed from the Puritans who came to this continent, but to a certain extent they were still governed by their ideas about work. Puritans believed that, “Idle hands (were) the devil’s workshop,” and that working hard was, “doing God’s work.” Things meant to entertain and amuse people – like reading novels, playing cards, and dancing – were morally suspect. Vacations would definitely have fallen under that category!

Victorian Era Americans were several generations removed from the Puritans who came to this continent, but to a certain extent they were still governed by their ideas about work. Puritans believed that, “Idle hands (were) the devil’s workshop,” and that working hard was, “doing God’s work.” Things meant to entertain and amuse people – like reading novels, playing cards, and dancing – were morally suspect. Vacations would definitely have fallen under that category!

Taking a holiday was out of the question for all but the idle rich before the middle to late 19th century. Prior to that, they were the only ones who had the leisure to do so, and the money to pay for it. Lack of transportation was a stumbling block, as was the absence of hotels, restaurants, and other vacation infrastructure. Another obstacle was the workweek, which was generally six days, with a day (or even just a half-day) off for church on Sundays. Weekends didn’t exist, and for the most part, neither did paid days off.

When the US government first tracked workers’ hours in 1890, full-time manufacturing employees were working around 100 hours per week. In 1910, President Taft suggested that Americans needed more time off to recuperate from the daily grind – two to three months of it, in fact. Unfortunately for us, Congress did not take the President’s suggestion to heart. They eventually did legislate the standard workweek and the minimum wage in the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 (which also banned child labor). Those were more in response to the Great Depression, though, and companies who had responded to it by slashing wages, making employees work much longer hours, and firing able-bodied adults in favor of hiring children who could be paid far less.

-

Troubled Travel

The Swindall Tourist Inn, Phoenix, AZ, was included as a safe place to stay in The Green Book.

Vacations have always been available only to those who can afford them. Many families couldn’t afford vacations, and to others (including this author’s while growing up), “taking a vacation,” meant going to visit family and staying in their home. For decades, though, vacations were prohibitive to many Americans simply because of the color of their skin. Trains, buses, gas stations, restaurants, hotels, and other businesses could refuse service to Black Americans because of the color of their skin, and often their safety and their very lives were in jeopardy because of the racism and hate they faced. Victor Green, a postal worker and American hero from Harlem, NY, changed that by taking it upon himself to create The Green Book. From 1936 to 1966, this essential guide listed businesses and even private homes that would welcome, do business with, and keep Black American travelers safe. The New York Public Library has 23 editions of The Green Book available online. It is an amazing resource, and we encourage you to explore their collection and think about those who had to use The Green Book to stay safe during their travels.

The fact that we’re able to go on vacation has its roots in labor history. But even further back, the growth of the middle class with its disposable income as well as the growth of the railroad industry affected our ability to take a holiday. Think about it – in 1876 (just seven years after the transcontinental railroad was finished), an “express” train traveled from New York City to San Francisco in 83 hours. That same trip would have taken months to complete in the decades prior (and, as anyone who played Oregon Trail as a kid knows, it would have been very dangerous — cholera and typhoid and bears, oh my!). Trains shortened travel time, and made visiting “far off places” possible.

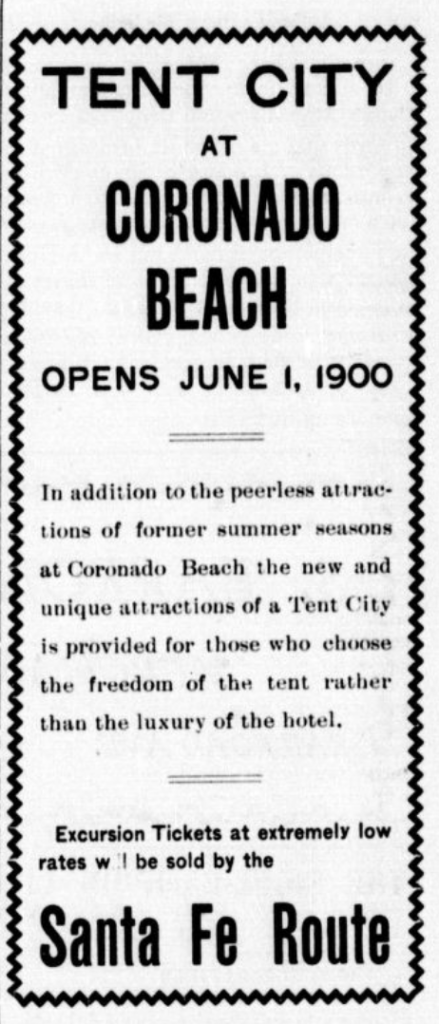

Many turn-of-the-century vacation destinations started out as health resorts, and grew as more people took time off work for their mental health as well as their physical wellbeing. The beach was a popular place to visit (on lakes inland as well as on the coasts) – as much for the cooler air in those un-air conditioned times as for the sea, sun, sand, and entertainment. Like Atlantic City’s famous Boardwalk, many coastal areas would see a boom in hotels, restaurants, and amusements for tourists. The same year that Rosson House was built, the Santa Fe, Prescott & Phoenix train could take you on a round trip from Phoenix to Los Angeles, Santa Monica, San Diego, and Coronado Beach for $15.95 in a sleeper car, stopping at Harvey Houses along the way. Coronado Beach boasted not only the grand Hotel de Coronado (c1888), but also a tent city (with over 1000 tents) where visitors who had less money to spend could stay, swimming facilities, an ostrich farm, carnival booths, a Ferris Wheel, aquaplaning, sailing, and a dance pavilion with a bandstand.

-

Higleys on Holiday

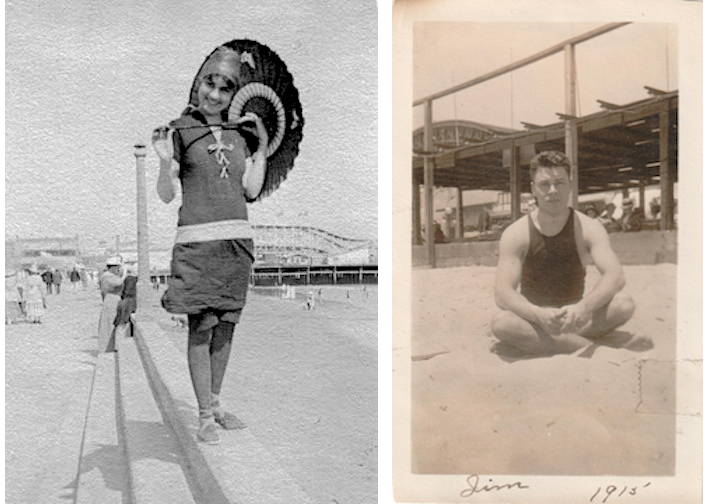

We know that the Higleys were likely the wealthiest family to own Rosson House. They had enough money to own two cars and two homes – their second was a summer home up in Flagstaff. Thanks to the Society section of the Arizona Republican, we also know they would spend their summers (and sometimes winters) from 1910 to 1916 in Long Beach, California, in a cottage they would rent for the season. The 1911 newspaper mentions Jessie Jean’s poor health, and that her stay in Long Beach helped her health improve (she was 16 years old at the time). We also have these great pictures of Jessie Jean and James Higley at Long Beach, showing off their fancy swimsuits (c1915).

If getting back to nature with mountains and streams was more your type of vacation, big things were happening on that front during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In 1872, Congress set aside land in the territories of Wyoming and Montana to create our country’s first national park, “for the benefit and enjoyment of the people” – Yellowstone. Many other national parks and monuments would follow, including the Grand Canyon as a national monument in 1908 and as a national park in 1919 (the National Park Service itself was created in 1916). Visitors found it difficult to visit many of these natural wonders until work was done to create roads, trails, and other infrastructure – peacetime army units, like the Buffalo Soldiers, did much of this kind of work (read about their park legacy online through the National Park Service). Many visitors arrived by train, but it was the advent of the automobile that really brought people to national parks in droves. Though campsites were available, grand lodges like El Tovar (Grand Canyon) and Old Faithful Inn (Yellowstone) were built to house the increasing number of visitors to the parks.

Vacations hit a stumbling block during the Great Depression, and again during World War II, but after the war ended, the number of people buying automobiles and taking vacations skyrocketed. Many Americans once again had the disposable income to take a holiday from work and school, and the tourism industry flourished, particularly along the famous Route 66.

Read more about the history of Arizona’s biggest and best economic driver, Climate, and how it attracted health-conscious visitors to our territory and state, on our blog.

Feel like getting away from it all? Take a musical trip around our nation’s natural wonders from this Library of Congress blog.

It was so much fun doing research for this article! Much of the information for this article was found from the book, Work at Play: A History of Vacations in the United States, by Cindy S. Aron. Information was also found online from the Coronado Historical Association, the US Department of the Interior, Smithsonian Magazine, The Atlantic, the Arizona Memory Project, the New York Public Library, The Economic Policy Institute, and the Library of Congress Chronicling America digital newspaper archive.