“While there is yet time I hasten to wish that you may take a dose of your own poison by mistake, and enter swiftly into the damnation which you and all other patent medicine assassins have so remorselessly earned and do so richly deserve.”– Mark Twain, in a letter dated November 20, 1905

Spin the bottle

Posted May 1, 2023

Written by Heather Roberts, Heritage Square,

and Zoë Garrett, Deer Valley Petroglyph Preserve

For a printable version of this article, please click here.

For a printable version of this article, please click here.

Did you know…

(For your convenience, at the end of the article there is a glossary of several of the medical terms used here.)

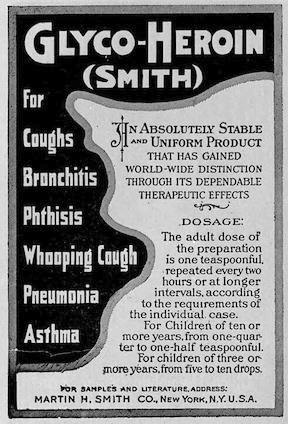

Bottles of restorative droughts, cures, and patent medicines were all the rage during the Victorian Era. For just a few pennies, you could buy something that was virtually guaranteed to treat any malady, ache, or pain, including everything from dysentery to deafness. There was just one problem – very few if any of the treatments actually worked. While some medicines contained herbs or plants that could be helpful or at least benign, most had ingredients that were addictive, like alcohol, cocaine, heroin, and opioids, or toxic, like mercury, strychnine, belladonna, and arsenic. An overall lack of medical knowledge together with few if any governmental regulations made self-medicating with these cures downright dangerous.

We’ve found a few medical bottles in our collection that are prime examples of these kinds of remedies:

-

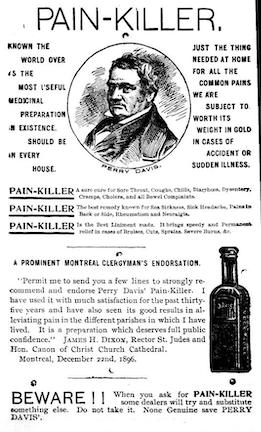

Perry Davis’ Pain Killer

Created by Perry Davis of Providence, RI, in 1839 and patented in 1845, it is likely one of the first medicines supposed to treat pain instead of a specific disease or illness. Billed as a “vegetable elixir” and an “all-natural wonder drug,” it contained mainly opioids and ethyl alcohol. Despite or maybe because of the elixir’s ingredients, it was marketed successfully worldwide as a remedy for both internal and external pain. When Perry died in 1862, his son Edmund continued the elixir business, and the pain killer is reported to have been given to soldiers and horses during the Civil War. At least some form of elixir was available up until 1958.

Created by Perry Davis of Providence, RI, in 1839 and patented in 1845, it is likely one of the first medicines supposed to treat pain instead of a specific disease or illness. Billed as a “vegetable elixir” and an “all-natural wonder drug,” it contained mainly opioids and ethyl alcohol. Despite or maybe because of the elixir’s ingredients, it was marketed successfully worldwide as a remedy for both internal and external pain. When Perry died in 1862, his son Edmund continued the elixir business, and the pain killer is reported to have been given to soldiers and horses during the Civil War. At least some form of elixir was available up until 1958.

-

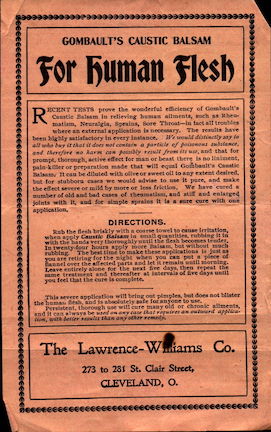

Gombault’s Caustic Balsam

Made according to a secret formula discovered in 1868 by J.E. Gombault, a veterinary surgeon of the French army. The Lawrence-Williams Co. of Cleveland, OH, were given exclusive rights to sell Gombault’s formula in the US and Canada in 1880. According to a 1911 Veterinary Medicine book, the secret formula was thought to contain croton oil, cotton seed oil, camphor, turpentine, kerosene, and sulphuric acid. The preparation was advertised to treat horses and cattle for, “curb, splint, sweeney, poll evil, grease heel, capped hock, strained tendons, founder, wind puffs, mange, skin diseases, swellings or ulcerations, lameness from spavin, ringbone and other bony tumors, and many other diseases or ailments.” (see glossary below for definitions) As you can see from the ad here, they also advertised it “for human flesh,” promoting it as a cure for rheumatism, neuralgia, sprains, and sore throats, as well as chest colds, backaches, lumbago, diphtheria, sore lungs, and still joints.

Made according to a secret formula discovered in 1868 by J.E. Gombault, a veterinary surgeon of the French army. The Lawrence-Williams Co. of Cleveland, OH, were given exclusive rights to sell Gombault’s formula in the US and Canada in 1880. According to a 1911 Veterinary Medicine book, the secret formula was thought to contain croton oil, cotton seed oil, camphor, turpentine, kerosene, and sulphuric acid. The preparation was advertised to treat horses and cattle for, “curb, splint, sweeney, poll evil, grease heel, capped hock, strained tendons, founder, wind puffs, mange, skin diseases, swellings or ulcerations, lameness from spavin, ringbone and other bony tumors, and many other diseases or ailments.” (see glossary below for definitions) As you can see from the ad here, they also advertised it “for human flesh,” promoting it as a cure for rheumatism, neuralgia, sprains, and sore throats, as well as chest colds, backaches, lumbago, diphtheria, sore lungs, and still joints.

-

Dr. Kilmer’s Swamp Root: Kidney, Liver & Bladder Remedy

Dr. Sylvester Kilmer established his laboratory and patent remedies company in Binghampton, NY the 1870s. By 1895, he was selling 18 different medicines, including Indian Cough Cure, Consumption Oil, Female Remedy (billed as “The Great Blood Purifier and System Regulator”), and Ocean Weed Heart Remedy. Swamp Root supposedly contained no fewer than 17 ingredients, including alcohol, buchu leaves, scullcap leaves, golden seal root, colombo root, valerian root, cinnamon, oil of juniper, oil of birch, balsam copaiba, balsam tolu, venice turpentine, peppermint herb, rhubarb root, mandrake root, sassafras, and cape aloes. Kilmer’s brother and nephew eventually took over the business, and the latter was quoted as answering the question, “What is Swamp Root good for?” with, “About a million dollars a year!” Some form of the Swamp Root remedy was still available in 1969.

Dr. Sylvester Kilmer established his laboratory and patent remedies company in Binghampton, NY the 1870s. By 1895, he was selling 18 different medicines, including Indian Cough Cure, Consumption Oil, Female Remedy (billed as “The Great Blood Purifier and System Regulator”), and Ocean Weed Heart Remedy. Swamp Root supposedly contained no fewer than 17 ingredients, including alcohol, buchu leaves, scullcap leaves, golden seal root, colombo root, valerian root, cinnamon, oil of juniper, oil of birch, balsam copaiba, balsam tolu, venice turpentine, peppermint herb, rhubarb root, mandrake root, sassafras, and cape aloes. Kilmer’s brother and nephew eventually took over the business, and the latter was quoted as answering the question, “What is Swamp Root good for?” with, “About a million dollars a year!” Some form of the Swamp Root remedy was still available in 1969.

-

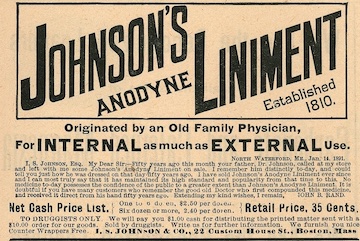

Johnson’s American Anodyne Liniment

The label on a bottle of Johnson’s Liniment reads, “For coughs, colds, grippy cold, colic, asthmatic distress, bronchial colds, nasal catarrh, cholera morbus, cramps, diarrhea, bruises, common sore throat, burns and scalds, chaps and chafing, chilblains, frost bites, muscular rheumatism, soreness, sprains and strains.” Johnson’s American Anodyne Liniment was created by Abner Johnson in Brewer, ME in 1810. Its ingredients included morphine, extract of Hyoscyamus (see glossary below), alcohol, and other ingredients. He sold this and his Indian Dyspeptic Bitters under the name A. Johnson & Son. After Abner’s death in 1847, his son, Isaac, eventually moved the business to Boston, MA, and changed the company name to I. S. Johnson & Co, where he sold Parson’s Purgative Pills and Sheridan’s Calvary Condition Powders.

The label on a bottle of Johnson’s Liniment reads, “For coughs, colds, grippy cold, colic, asthmatic distress, bronchial colds, nasal catarrh, cholera morbus, cramps, diarrhea, bruises, common sore throat, burns and scalds, chaps and chafing, chilblains, frost bites, muscular rheumatism, soreness, sprains and strains.” Johnson’s American Anodyne Liniment was created by Abner Johnson in Brewer, ME in 1810. Its ingredients included morphine, extract of Hyoscyamus (see glossary below), alcohol, and other ingredients. He sold this and his Indian Dyspeptic Bitters under the name A. Johnson & Son. After Abner’s death in 1847, his son, Isaac, eventually moved the business to Boston, MA, and changed the company name to I. S. Johnson & Co, where he sold Parson’s Purgative Pills and Sheridan’s Calvary Condition Powders.

-

William Radam’s Microbe Killer

William Radam, a German gardener and botanist who moved to Austin, TX, was inspired by his own illness and the deaths of two of his children when in 1866 he patented a “Microbe Killer” that he claimed would “cure all diseases.” Its ingredients were powdered sulfur, sodium nitrate, manganese oxide, potassium chloride, sandalwood, and red wine. In 1890, Radam wrote a book about his experience in creating his patent remedy and how to use it, called Microbes and the Microbe-Killer. In it he claimed that large doses of his medicine could cure leprosy, consumption, malaria, and cancer. In reality, it did nothing. When laws were passed prohibiting medicines from claiming fraudulent curative powers, Radam’s Microbe Killer was one of the first medicines to be successfully prosecuted.

William Radam, a German gardener and botanist who moved to Austin, TX, was inspired by his own illness and the deaths of two of his children when in 1866 he patented a “Microbe Killer” that he claimed would “cure all diseases.” Its ingredients were powdered sulfur, sodium nitrate, manganese oxide, potassium chloride, sandalwood, and red wine. In 1890, Radam wrote a book about his experience in creating his patent remedy and how to use it, called Microbes and the Microbe-Killer. In it he claimed that large doses of his medicine could cure leprosy, consumption, malaria, and cancer. In reality, it did nothing. When laws were passed prohibiting medicines from claiming fraudulent curative powers, Radam’s Microbe Killer was one of the first medicines to be successfully prosecuted.(In the photo, Radam’s Microbe Killer is the brown bottle on the right, and Gombault’s Caustic Balsam is the small, clear bottle on the left.)

-

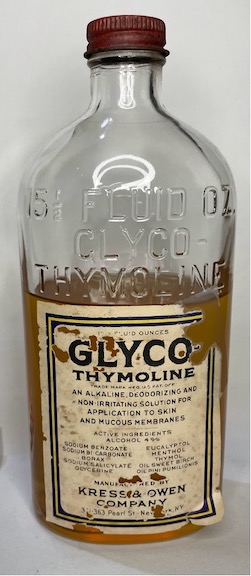

Glyco-Thymoline

Created in 1890 by pharmacists Samuel Owen and Oscar Kress as a treatment for cuts, burns, and skin irritations, its ingredients included menthol, pine and birch oils, and borax – a naturally occurring mineral commonly used today in household cleaners, laundry boosters, and pesticides. In the 1910s it began being used as a treatment that people would ingest or run through their nasal passages in order to cure internal irritations, such as post-nasal drip or mouth/gum abscesses. In 1912 it was hailed in Sydney, Australia’s Dental Review as a treatment for “Alveolar Abscess,” “Spongy Gums,” and that it “is especially serviceable as a mouthwash after extractions.” When this particular brand of Glyco-Thymoline was manufactured, it was primarily used as a treatment for sore throats and to maintain an overall healthy mouth.

Glyco-Thymoline is still being sold today, and one of the main ingredients of modern Glyco-Thymoline is sodium borate, which is a different name for borax. Ingestion and overexposure to borax are known to cause headaches, nausea, dizziness, tremors, and unconsciousness. Borax is not safe for children, and even when handling borax one should always wear gloves and protect oneself from direct contact with it. Glyco-Thymoline is not and has never been approved by the FDA, and we at Heritage Square do not recommend trying Glyco-Thymoline for yourself.

(Photo Caption: This bottle of Glyco-Thymoline was found in a septic tank near Rosson House during its restoration in the 1970s, along with a number of other assorted bottles and items. It is believed to have been manufactured sometime in the late 1920s or early 1930s.)

Manufacturers of patent medications often adopted names that made them seem more trustworthy, adding “Doctor” or “Professor” to a name (regardless of their actual title) and/or adding false testimonials from doctors or reverends. Marketing for these remedies were also often misleading, not only making claims of curative powers for a wide range of completely unrelated maladies (like Radam’s claims to cure both colds and cancer), but also with the images they used. On labels, ads, and trade cards they used images of white women and children to promote feelings of innocence, and healthy, happy families, connecting those feelings to their products (despite their ingredients). Images of people of other races or ethnic groups were only included as caricatures of stereotypical, racist viewpoints: Imagery of and language referring to Native Americans in products was meant to evoke a deeper knowledge of plants and nature; people of color were negatively stereotyped in ads meant to ridicule; and images of people from Asia were used to promote mysterious and exotic ingredients. In all these instances, the manufacturers were simply exploiting these stereotypes for profit.

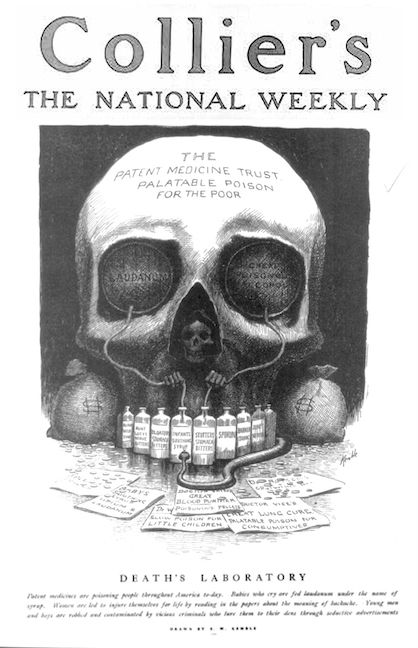

By the turn-of-the-century, people’s trust in these patent medicines was waning. At the same time work from Dr. Harvey Wiley, Chief Chemist of the US Department of Agriculture, brought to light the adulteration of food, there was also pushback against fraudulent and adulterated medicines by doctors, pharmacists, and in the press. Collier’s The National Weekly took a stand with illustrations in their magazine (seen here), and with a series of 11 articles written by American “muckraker” journalist, Samuel Hopkins Adams, on the topic of patent medicines under the title, “The Great American Fraud.” In these articles he calls out fraudulent hucksters, charlatans, “miracle” workers, and quacks by name (and sometimes with their actual photos), detailing their lies, documenting the dangerous effects of their products, and calling on people in positions of power to do something about it.

By the turn-of-the-century, people’s trust in these patent medicines was waning. At the same time work from Dr. Harvey Wiley, Chief Chemist of the US Department of Agriculture, brought to light the adulteration of food, there was also pushback against fraudulent and adulterated medicines by doctors, pharmacists, and in the press. Collier’s The National Weekly took a stand with illustrations in their magazine (seen here), and with a series of 11 articles written by American “muckraker” journalist, Samuel Hopkins Adams, on the topic of patent medicines under the title, “The Great American Fraud.” In these articles he calls out fraudulent hucksters, charlatans, “miracle” workers, and quacks by name (and sometimes with their actual photos), detailing their lies, documenting the dangerous effects of their products, and calling on people in positions of power to do something about it.

Prior to federal regulation, some individual municipalities and states enacted laws regulating or banning certain medications. San Francisco, CA and Lexington, KY banned a drug called Liquozone (supposedly made of liquid ozone, but in reality a combination of water and both sulfuric and sulfurous acid), and Illinois passed a law that required any medications containing cocaine be available by prescription only, and to be labeled with the total amount of cocaine included.

The 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act prohibited the manufacture, sale, or transportation of tainted, misbranded, poisonous, or harmful drugs/medicines, based on what was specifically claimed on their labels. It also required manufacturers to mention if their drugs included alcohol, morphine, opium, cocaine, heroin, eucaine (an anesthetic), chloroform, cannabis, chloral hydrate (a sedative), or acetanilide (a pain reliever). An amendment in 1912 added a prohibition against false curative claims, but neither regulated a drug’s safety or efficacy. When the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938 was passed, the new law finally required manufacturers prove to the FDA (Food and Drug Administration) that their medicines were safe before they could be sold to the public.

-

Glossary

Terms in this glossary were found in the dictionary unless otherwise identified.

Alveolar (adjective) – Of, relating to, or constituting the part of the jaws where the teeth arise.

Anodyne (adjective) – Serving to alleviate pain.

Balsam (noun) – A medical preparation containing resinous substances and having an aromatic, balsamic odor.

Capped hock (noun) – A swelling over the point of a horses hock (joint on the hind leg). (Jonathan Wood Veterinary Surgeon)

Catarrh (noun) – A build-up of mucus in an airway or cavity of the body, also called post-nasal drip.

Caustic (noun) – A substance that burns or destroys organic tissue by chemical action.

Chilblains (noun) – Small, itchy swellings on the skin that occur as a reaction to cold temperatures.

Founder (noun) – Also known as laminitis, founder is inflammation of the laminae (soft tissue structures) of the foot of the hoof wall. (RSPCA Australia)

Greasy heel (noun) – Also known as pastern dermatitis, greasy heel is an inflammatory condition of the skin involving the lower limbs, particularly the non-pigmented skin. (Canberra Equine Hospital)

Hyoscyamus (noun) – Also known as henbane, hyoscyamus is a plant genus that consists of about 20 species and all of them contain powerful narcotic tropane alkaloids. Ingestion of hyoscyamus plants can cause loss of muscular control, dilation of the pupils, heart palpitation, hallucinations, delirium, and in large doses, coma, and death. (US Forest Service)

Liniment (noun) – A liquid or semiliquid preparation that is applied to the skin as a pain killer or a counterirritant.

Nostrum (noun) – A medicine sold with false or exaggerated claims and with no demonstrable value.

Poll evil (noun) –A painful condition in a horse or other equid, that starts as an inflamed bursa at the cranial end of the neck between vertebrae and the nuchal ligament, and swells until it presents as an acute swelling at the poll, on the top of the back of the animal’s head.

Spavin (noun) – Also known as degenerative joint disease or distal tarsitis, bone spavin is an osteoarthritis and periostitis of the distal intertarsal, tarsometatarsal, and occasionally the proximal intertarsal joints of a horse. (South Shore Equine Clinic)

Splint (noun) – A hard, bony swelling that appears on the inside (or occasionally outside) of the horse’s lower leg. (Horse Health Programme, UK)

Sweeney shoulder (noun) – A condition recognized by atrophy or “wasting away” of the muscles that are located in the shoulder area. Over 100 years ago Sweeney was caused by the heavy harnesses that the horses had to wear while pulling carts/buggies, as horses were the primary source of transportation. (River Road Veterinary Clinic)

Windpuffs (noun) – A general term designating non-specific swelling around the fetlock area (directly above the hoof) of the horse, typically along the back of the limb. (Atlanta Equine Clinic Client Education Library)

Learn more about turn-of-the-century medicine from our March 2019 blog article, Victorian Cures & Quacks, and about the history of food preservation from our April 2021 blog article, Can It!.

Explore these online exhibits about turn-of-the-century medicine – the University of St. Augustine for Health Sciences Library exhibit, Cures and Curses: A History of Pharmaceutical Advertising in America; the Virtual Museum of Historical Bottles and Glass: Medicine Gallery; and the Digital Public Library of America exhibit, Quack Cures and Self-Remedies: Patent Medicine.

Read Samuel Hopkins Adams’s “The Great American Fraud” articles in these editions of Collier’s The National Weekly, courtesy of the Internet Archive:

-

-

- Volume 36, Issue 2, October 7, 1905 (p14) – The Great American Fraud

- Volume 36, Issue 5, October 28, 1905 (p16) – Peruna & the “Bracers”

- Volume 36, Issue 8, November 18, 1905 (p20) – Liquozone

- Volume 36, Issue 10, December 2, 1905 (p16) – The Subtle Poisons

- Volume 36, Issue 16, January 13, 1906 (p18) – Preying on the Incurables

- Volume 36, Issue 21, February 7, 1906 (p22) – The Fundamental Fakes

- Volume 37, Issue 5, April 28, 1906 (p16) – Warranted Harmless

- Volume 37, Issue 16, July 14, 1906 (p12) – Quacks & Quackery I: The Sure-Cure School

- Volume 37, Issue 19, August 8, 1906 (p14) – Quacks & Quackery II: The Miracle Workers

- Volume 37, Issue 23, September 1, 1906 (p16) – Quacks & Quackery III: The Specialist Humbug

- Volume 37, Issue 26, September 22, 1906 (p16) – Quacks & Quackery IV: The Scavengers

-

Information for this article was found online at the links listed above and throughout the article, as well as the Museum of Healthcare (Kingston, ON, Canada) – The Story of Perry Davis and His Painkiller (blog), Dr. Kilmer’s Swamp Root; William Radam’s Microbe Killer, and Glyco-Thymoline; the Rhode Tour – 1862: Perry Davis’ Vegetable Pain-Killer; the Smithsonian National Museum of American History – Balm of America: Patent Medicine Collection, Dr. Kilmer’s Swamp Root, and Glyco-Thymoline; the National Park Service – Dr. Kilmer’s Medicine Bottle; ScienceDirect – Pure Food and Drug Act; the National Endowment for the Humanities Magazine – Dr. Kilmer’s Curious Cure-All; the Cooperstown Graduate Program CGPArtifact blog – Microbe Malpractice; Chronicling America digital newspaper archive; Peachridge Glass – Dr. Johnson’s Indian Dyspeptic Bitters, Wm. Radam’s Microbe Killer; Racehorse Herbal – Gombault’s Caustic Balsam; the Glyco-Thymoline website; Art of the Print – Gombault’s Caustic Balsam Trade Card; Old Main Artifacts – Liquozone Company, Chicago; the Meyer Bros. Druggist, volume XXIV, 1903 (p378) – The Cocaine Regulations; and US Food & Drug Administration – Part II: 1938 Food, Drug, Cosmetic Act.

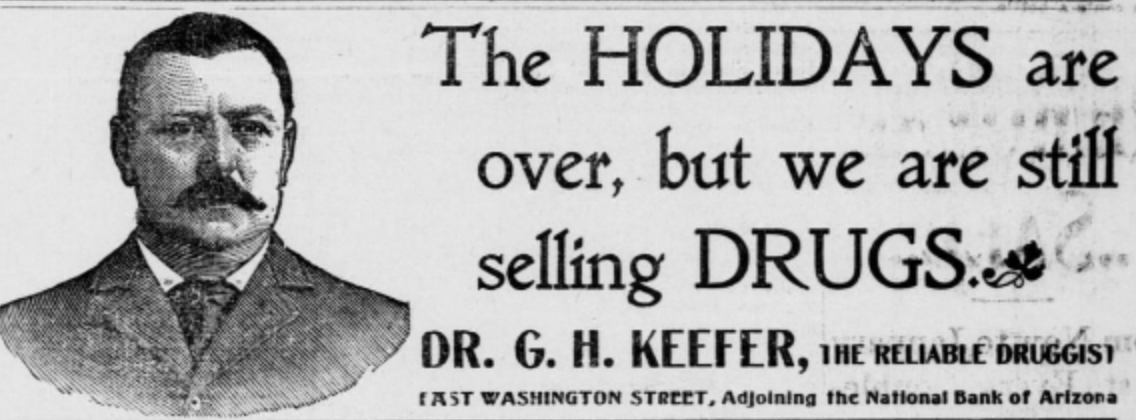

Thank you for reading this far! As a thank you, we’re sharing our favorite medical ad from the December 31, 1899 edition of the Arizona Republic:

Archive

-

2025

-

January (1)

-

-

2024

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2023

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2022

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

-

2021

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2020

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2019

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2018

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

January (1)

-

-

2017

-

December (1)

-

November (1)

-

October (1)

-

September (1)

-

August (1)

-

July (1)

-

June (1)

-

May (1)

-

April (1)

-

March (1)

-

February (1)

-

-

2016

-

December (1)

-

-

2015

-

2014

-

July (1)

-